Arts & Culture

Poet Maurice Manning: A Voice in the Wilderness

Part Appalachian storyteller. Part modern-day Thoreau, Manning has carved out his own spot in the pantheon of American poets from a twenty-acre swath of Kentucky woods

Photo: Eric Ryan Anderson

While at work on his most recent collection, One Man’s Dark, the poet Maurice Manning began to have vivid dreams. In one, he traveled to the Eastern Kentucky farm where his great-grandmother Lillian was raised. Standing in a dark barn, Manning saw sunlight sifting between the old wooden boards. He walked through a dogtrot, then out a door at the back of the barn. A meadow opened up, and there his great-grandmother, dead since 1980, appeared to him—as a little girl. Manning interprets the dream this way: “She was saying, ‘This is where I always am.’” But there’s more. A few years after the dream, to his surprise, Manning became a father for the first time at forty-nine. “I believe it’s some kind of mystical thing that my great-grandmother appeared to me as a little girl,” he says, “and then several years later we have our own little girl rather unexpectedly.” Her name is Lillian.

Photo: Eric Ryan Anderson

A tobacco barn more than a century old sits on the property.

When I arrive at Manning’s modest white farmhouse in rural Washington County, Kentucky, his wife, Amanda, is just putting Lillian, who is now three years old, down for her nap. An older, infirm Lab mix limps over to me. “Hey buddy,” I say, scratching his head.

“That’s his name!” Manning says, beaming. He flashes a quick smile through a thin beard and leashes a beagle named Cap. Both dogs just wandered into Maurice and Amanda’s lives, owners nowhere in sight. Strays, I learn, are more or less constantly moving through the Manning house.

It’s a gray day typical of Kentucky winters, but Manning, built like a seasoned walker, pulls on a heavy coat, and we, along with Cap, head out to circumambulate his small farm. Behind a generations-old barn, several garden plots spread into a clearing that soon gives way to a woodlot of hickories, locusts, oaks, and hornbeams—signature trees of Central Kentucky. Previous owners had abused the soil, so Manning has slowly been amending it with compost and lime. Last year his okra grew to fifteen feet, though he acknowledges that pruning would have made the plants more productive. “My gardening is very similar to my endeavors in poetry,” Manning says. “None of it is precise, but all of it satisfies a curiosity, even a hope.”

To understand Manning’s decision to put down roots on this twenty-acre parcel of Kentucky’s Inner Bluegrass, you have to go back a few generations. Manning comes from a long line, on his father’s side, of self-sufficient Eastern Kentuckians. “They provided for themselves instead of living on a paycheck,” he remembers. He speaks slowly, deliberately, and one gets the sense that every word is carefully weighed before it rises to the level of speech.

Manning’s father, Alex, was raised by his grandmother Lillian and his grandfather Alexander on a small farm called Dun Romin (as in “Done Roaming”) near Tyner, Kentucky. But following Alexander’s sudden death from a heart attack in 1945, Lillian had to sell the farm and relocated with Manning’s father to a one-room apartment in Lexington. “By now Dad was a teenager, and I think he pretty much roamed the streets,” Manning tells me. Eventually, Alex dropped out of school and joined the navy. When he returned from three tours in Korea, he and Manning’s mother, Gail, married and moved to the small town of Danville, Kentucky, where Maurice was raised. But life in town seemed to bewilder Manning’s father and left him, in Manning’s words, “itinerant and deeply lonely.” Manning came to lay the blame for some of his father’s troubles on that sudden break from rural life back in ’45. “I knew early on that it was my obligation to return my family’s connection to the land,” he says as we walk along a dry creek bed lined with cedars.

Photo: Eric Ryan Anderson

The farmhouse Manning renovated himself.

Manning told himself that if he ever made any money as a writer, he would buy a small farm in Kentucky. Then in 2001 he won the prestigious Yale Series of Younger Poets award for his first book, Lawrence Booth’s Book of Visions. There is, of course, little money in selling books of poetry, but because of the prize, Manning was offered enough reading gigs to make a down payment on these twenty acres.

The farmhouse was uninhabitable, so Manning tore it down to the studs and began a major renovation by himself. His former Boy Scout adage, “learn by doing,” set him to work running electric, hanging Sheetrock, and replacing layers of newspaper dating to 1905 with actual insulation. He was teaching then in Indiana, but he spent his weekends and summers here, toiling away on the house and writing poems. Two more collections followed, and in 2010, he published the book that would become a Pulitzer finalist, The Common Man.

That collection is quite unlike anything else in contemporary American poetry. For one thing, it draws on the Appalachian tradition of Jack Tales—narrative stories that are alternately rollicking, comic, gothic, and melancholy.

In one hilarious poem, “A Wringer Washer on the Porch,” a woman preaching temperance appears at the home of a confirmed bachelor who “did not take kindly to the wrath / of a woman he didn’t even know.” Somehow the woman’s apron strings end up caught in said wringer washer (just the size for concocting a batch of homemade wine). The woman screams herself hoarse to be set loose until the homeowner “convinced her that a little wine / might soothe her throat and he was right.” Serious porch dancing commences. You can probably guess the rest.

Many poems in The Common Man, as well as in Manning’s next two collections, are like that: stories that feel handed down through an oral tradition, often written in four-beat lines because, as he says, “that’s just the pace of the phrase that I hear.” Manning, who writes longhand in an unlined sketchbook, emphasizes the difference between what he calls spoken language and thought language. “I often fear our spoken language is losing its spunk,” he says, “so I feel an obligation to keep it alive.”

The narrator of one poem in The Common Man asks, “You reckon I could ever run out / of stories in my heart to tell?” For Manning, who seems like a spring-fed reservoir of such stories, it appears unlikely. This fall he will publish his seventh book, Railsplitter, a sequence of poems narrated from the grave by fellow Kentuckian Abraham Lincoln, whose grandfather owned land nearby. At his day jobs, Manning teaches in the MFA program at Warren Wilson College in North Carolina and closer to home at Lexington’s Transylvania University. But where do all those stories come from?

Photo: Eric Ryan Anderson

Manning during a walk at Perryville Battlefield, a Civil War site near his home.

“When I was growing up in Danville, I was acquainted with the old-timers,” Manning explains. “I didn’t have any problem sitting and talking to an eighty-year-old woman.” As a boy, he shined shoes at the local barbershop, had a paper route, and later worked at the hardware store—all fertile ground for tales. “It took me forever to deliver the paper because these pretty lonely people wanted me to come in and talk,” he remembers. “For whatever reason, I was lucky enough to be there and pay attention.”

And that’s what Manning is—a listener, a song catcher with an ear perfectly tuned to native speech (as in this wonderfully coarse four-beat phrase: “slicker than a minner’s peter”). Imagine any other major American poet beginning a poem with this line: “A mind unhitched to a heart?—Shuckies!” Indeed, Manning’s work is unfashionably traditional, even as it is wildly inventive. In an age of irony, it takes a certain confidence, even courage, to write like this. Manning admits to a preference for older ways, and that leads to an inevitably elegiac quality in his work. The title poem of his fifth collection, The Gone and the Going Away, begins,

The world I know keeps going farther

and farther away. I cannot keep it

from going, though I love it still,

and yet, with darker joy….

These twenty acres feel like both a real and a symbolic bulwark between a receding life of authenticity and the digital realm of vicarious experience. “There are things about the modern world that I am not going to get on board with,” Manning says as we pause to admire a persimmon tree that figures into several of his poems. “I’d like to live with minimal connection to it if possible.”

A reader will find no mass-produced objects in a Maurice Manning poem, and seldom anything man-made at all, save the language itself. As the narrator of “The Dream of a Mountain Woman Big Enough for Me” asserts,

I like

the things that come into the world

already made, like a birdsong or

the purple on a pokeweed stem,

the humble things that humble all

the rest….

The things that come into the world to be bought and sold, Manning tells me, “don’t even seem like things. If it’s something that winds up in a landfill after eighteen months, it doesn’t have any lasting quality, so why would it have any literary quality?” Then he looks up at the tree. A guitar player like his great-grandfather, Manning muses, “I’d like to have a dulcimer made out of persimmon wood.”

We wander on up the hill, toward the back of Manning’s property. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche said that all thoughts of value are conceived while walking, and for Manning, this is often how a poem begins. The earliest “literary experience” he remembers happened when he was eight and his grandparents gave him a tape recorder “about the size of a shoebox,” he says. He would go traipsing through the woods near his house and make up stories as he went. When the tape came to the end, he’d turn it over, turn around, and tell more stories as he retraced his steps home. After dark, he would sit by himself and listen to the recording. “I don’t know why I did that,” he says, spreading his arms as if for an answer. “But the idea of walking in the woods and being imaginative was an instinct I had at an early age.”

That combination has led to a deeply metaphysical vein of Manning’s poetry. In one poem his narrator asks, “…can you think / of anything more true than the God /who goes on living in a tree?” For Manning, an obvious child of Thoreau and the transcendentalists, the laws of heaven and the laws of the heart can only be read in the Book of Nature.

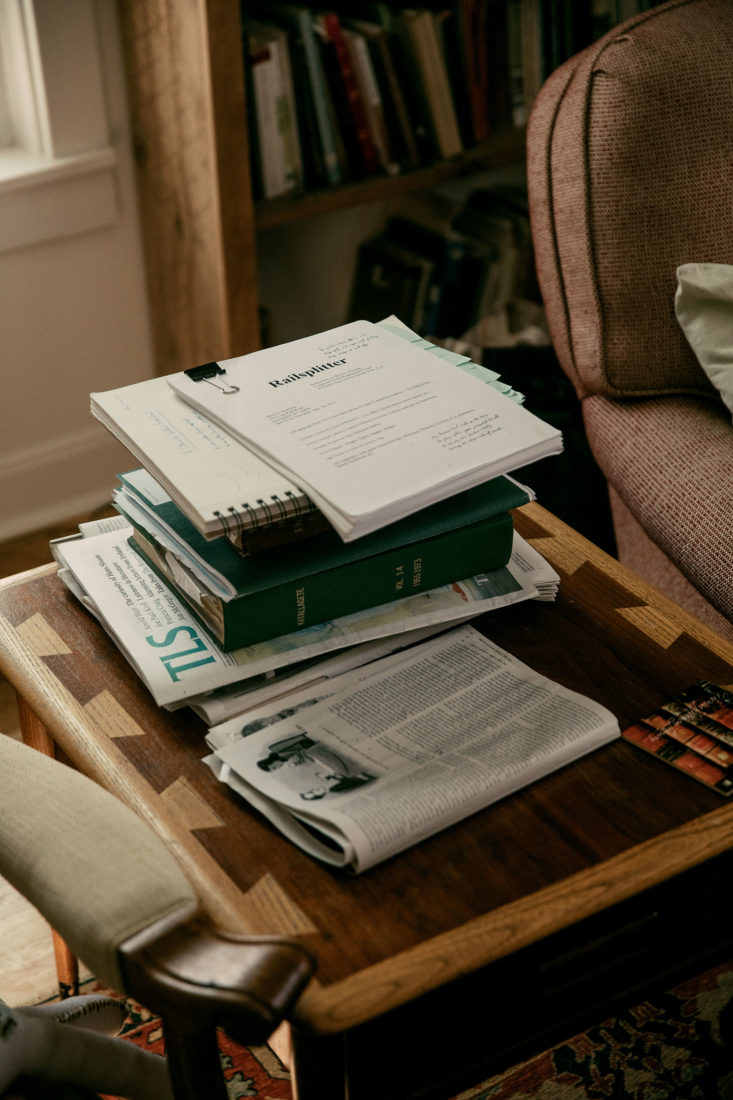

Photo: Eric Ryan Anderson

The poet’s reading pile.

But when I hazard that he might in some way be a religious poet, Manning flinches slightly at the idea. “I don’t write poems to have a religious message or to preach,” he says. “The religious element gets into my work because I’m asking questions. That’s what poetry does for me. It’s a means to wonder. Finding the answer isn’t the point. Expressing the wonder is the point.”

Still, Manning says he has always been drawn to the religious symbolism of wandering in the wilderness. It’s the kind of isolation that has shaped his own poetic voice. In an autobiographical poem called “Southern City Poem, Early ’70s,” from One Man’s Dark, Manning’s mother drives him into Lexington as a boy and sends him into various bars to go look for his father, who is nowhere to be found. It’s raining and the boy’s pajamas get soaked as he waits on the sidewalk for his mother to come back and pick him up.

I was alone with being alone,

but luckily, I must have been seven

or eight, so I got started young

on poetry and all that.

The poem ends,

…and then I grew up, and some of the time

I wasn’t alone, but most of the time

I was, so I became the king

of that infinity and rain.

It’s a heartrending poem about how what Manning calls “the bad kind of being alone” can be transformed into the solitude that incubates poetry.

Now, however, Manning the solitary rain king has become Manning the husband and father. But he hasn’t given up on his guiding ethos. “Amanda and I share a particular solitude living where we do,” he tells me back at the house, where he gathers up firewood to replenish the woodstove. “I’m realizing that being comfortable with quiet is something we can teach our daughter. And it will be part of her too.”

Yet while Manning shares a clear affinity with the Shakers who once lived just up the road at Pleasant Hill, it isn’t all solemnity and silence. A few weeks earlier, he had gone into an antique store looking to buy a Christmas present for Amanda. Instead he came out with a vintage ’64 acoustic Gibson.

After rebuilding the fire, he fetches the guitar and, sitting at the kitchen table, bangs out a boisterous version of his daughter’s favorite song, the Beatles’ “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.” Lillian dances in gleeful spasms, then rolls around on the floor with arms flailing until Amanda scoops her up and announces bath time, and they both disappear upstairs.

Photo: Eric Ryan Anderson

Manning plays a tune for his daughter.

“I feel like everything I try to do as a writer is suddenly larger and more is at stake,” Manning says of being a father. “I realize this is something I can give my daughter, some quality, some ethic, some sense of working with a skill. Whatever she does with herself, she hopefully will benefit from having a particular example. And hopefully that will make her life one she lives with a little more stability and confidence.”

His age also plays inevitably into Manning’s thoughts about Lillian’s future. “Because we had our child relatively late,” he continues, “I also feel like I don’t know how much of this I’ll be able to tell her face-to-face, and if there’s something in the work, in the poetry, she can grasp, she’ll at least have that.”

In a recent New York Times interview, the renowned Kentucky farmer and writer Wendell Berry expressed his pleasure that a younger generation of Kentucky writers—he cited Manning and the novelist Silas House—have decided to settle down in their home state to work. House hosts a sprawling Appalachian literature symposium at Berea College every two years, and in 2017 Manning gave the keynote address, urging the audience to “trust the literary qualities of your home culture.” While the larger world frequently lampoons Appalachia as a region and a people, Manning concluded with this: “My inclination is to get more hillbilly as I go, to challenge the status quo, to push back against the establishment, as any artist must, and see what happens. Let us carry on with our work.”

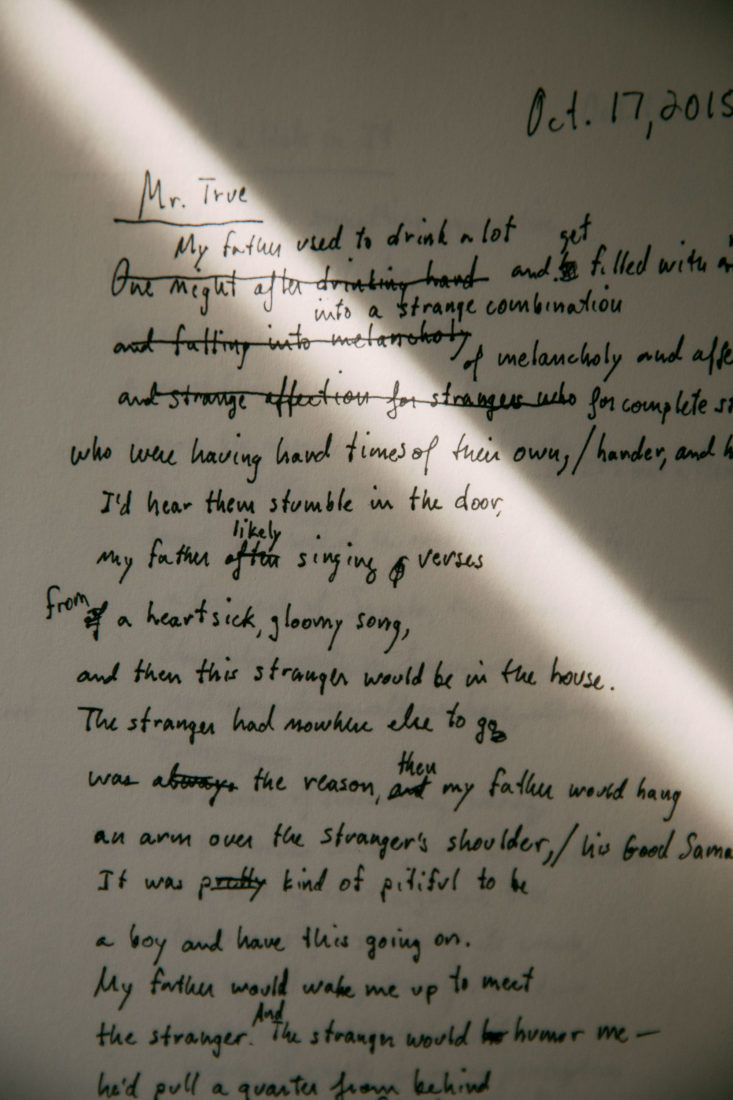

Photo: Eric Ryan Anderson

A page in Manning’s notebook, in which he composes poems longhand.

Manning is carrying on with Railsplitter, his series of Lincoln poems. Back on the four hundredth anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, in 2016, the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., asked Manning to make a video in commemoration. He got the idea to visit Sinking Spring, Lincoln’s birthplace, and read the passage from Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in which the fraudulent duke and king make a hash out of the famous soliloquy—“To be, or not to be; that is the bare bodkin”—on Huck and Jim’s raft.

“I realized that’s the kind of theater Lincoln would have first been exposed to,” Manning says. “Almost a sideshow thing. And yet there was something in it nevertheless. That he came from such a humble experience is just amazing. He was by far our most literary president and he went to less than a year of school. Yet he made something of himself in a way that so many of our presidents haven’t had to do.”

Was Manning thinking about someone, you know, in particular? “I really tried not to use my imagining of Lincoln as a commentary on our current circumstances,” he says. “In some ways, by holding up a counterexample of what we’ve got, you really don’t have to say much about what we’ve got.”

Sitting with Manning in his small, book-lined living room, I get the sense that he isn’t too bothered by the frenetic absurdity of today’s political circus. Like his hero, Robert Penn Warren, one of the Southern Agrarian writers who collaborated on I’ll Take My Stand, a manifesto on the value of rural life, Manning has placed his bets elsewhere. As he writes in the final poem of The Common Man,

There’s hope

in a world that’s slowly happening,

according to its own design.

Eric Ryan Anderson

On Silence

Poetry is the art of silence,

the art of knowing when to stop

a word or phrase and let it hang

like a sheet billowing on the line.

And the sudden or unexpected silence

goes hand in hand with what is said

in words or the flowery, natural phrase.

Beginning with the idiom

and moving to the metaphor,

while following the stark rhythms

of thought as they proceed and follow,

is elegance, a wave of the hand

for dancers to come forth and dance

and give the scene a fluid movement.

I see it all in a grand entrance,

meaning I see it as entrancing,

rapt and enthralling all there is.

But what, in fact or dainty figure,

is the scene? People in dark and bright

attire coming closely together

for a dance, for a spinning exultant reel?

I made myself present for such

events, yet also removed myself,

to step away to pause and reflect.

And stepping away I learned my candor,

I learned how to pass my time in a phrase,

in a measured phrase of poetry,

and that is where I’ve tried to live.

—Maurice Manning, from his forthcoming collection, Railsplitter